The Ilen River enters the sea at Ireland’s southwest corner, to the north of Baltimore Harbour. The river offers several anchorages on its north-eastward path to Skibbereen, the chief town of the area, situated seven miles above its entrance. Oldcourt is located four miles from the river mouth and provides a river anchorage plus the option to come alongside a local boatyard's pontoon or barge.

Set deep within a narrow river Oldcourt offers complete protection from all wind directions. Careful navigation is required when operating in the River Ilen most especially at the river mouth. The river can be entered directly from Long Island Bay or from the north end of Baltimore Harbour, and in either case, there is little in the way of supporting marks and it can involve significant pilotage. Narrow, shallow at times and with ample rocks to circumvent be prepared for some keen eyeball navigation supported by excellent visibility.

Keyfacts for Oldcourt

Last modified

November 19th 2021 Summary* Restrictions apply

A completely protected location with careful navigation required for access.Facilities

Nature

Considerations

Position and approaches

Expand to new tab or fullscreen

Haven position

51° 32.090' N, 009° 19.240' W

51° 32.090' N, 009° 19.240' WIn the middle of the river opposite the boatyard.

What are the initial fixes?

The following waypoints will set up a final approach:(i) River Ilen Entrance Initial Fix

51° 28.575' N, 009° 26.404' W

51° 28.575' N, 009° 26.404' WThis is set on the clearing line of bearing 230°T of Clare Island's Doonanore Castle ruins open east of Illauneana, as best seen on Admiralty 2129.

(ii) Baltimore Harbour initial fix

51° 28.120' N, 009° 23.423' W

51° 28.120' N, 009° 23.423' WThis is a quarter of a mile due south of the entrance, midway between Beacon & Barrack Point in the white sector of the lighthouse.

What are the key points of the approach?

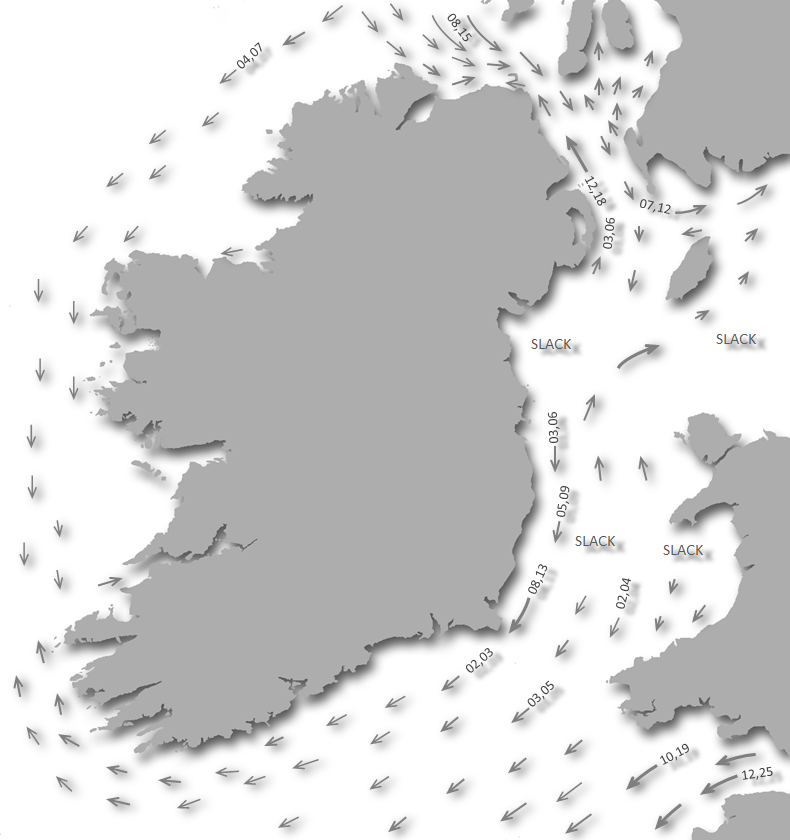

Offshore details are available in southwestern Ireland’s Coastal Overview for Cork Harbour to Mizen Head  .

.

.

. Not what you need?

Click the 'Next' and 'Previous' buttons to progress through neighbouring havens in a coastal 'clockwise' or 'anti-clockwise' sequence. Below are the ten nearest havens to Oldcourt for your convenience.

Ten nearest havens by straight line charted distance and bearing:

- Reena Dhuna - 1.9 nautical miles WSW

- Inane Creek - 2.6 nautical miles SW

- Barloge Creek (Lough Hyne) - 2.7 nautical miles SSE

- Baltimore - 3.7 nautical miles SSW

- Poulgorm Bay - 3.7 nautical miles W

- Quarantine Island - 3.8 nautical miles SW

- Ballydehob Bay - 4.2 nautical miles W

- Turk Head - 4.2 nautical miles SW

- East Pier - 4.3 nautical miles WSW

- Rincolisky Harbour - 4.3 nautical miles WSW

These havens are ordered by straight line charted distance and bearing, and can be reordered by compass direction or coastal sequence:

- Reena Dhuna - 1.9 miles WSW

- Inane Creek - 2.6 miles SW

- Barloge Creek (Lough Hyne) - 2.7 miles SSE

- Baltimore - 3.7 miles SSW

- Poulgorm Bay - 3.7 miles W

- Quarantine Island - 3.8 miles SW

- Ballydehob Bay - 4.2 miles W

- Turk Head - 4.2 miles SW

- East Pier - 4.3 miles WSW

- Rincolisky Harbour - 4.3 miles WSW

What's the story here?

Oldcourt and its various berths

Oldcourt and its various berthsImage: Michael Harpur

Oldcourt is located on a bend of the River Ilen, locally pronounced Eye-len, 4½ miles above the entrance and between the town of Skibbereen and Baltimore Harbour. It is marked by the ruins of an old castle that stands on the south side of the river set on a sloping rock that forms the end of a low rocky promontory. The river then bends abruptly northward around the opposite headland where it is flanked by a sizable boatyard sited on the eastern shore. From here, in about ¾ of a mile, the river narrows and shallows to a stream that continues in a north-easterly direction to Skibbereen 2½ miles above.

Yacht moored upriver of Oldcourt

Yacht moored upriver of OldcourtImage: Michael Harpur

Oldcourt river is ¾ of a mile above a limiting depth of 0.8 of a metre LAT located in the upper reaches to the northeast of Inishbeg Island. But is otherwise more than serviceable to moderate draft leisure craft most of the time. Depths of 2.7 metres LAT can be found off of Oldcourt but it shallows to a little over 1 metre LAT about 250 metres further northward. Anchor in the river in the vicinity of the boatyard clear of its operations.

Yacht alongside the pontoon at Oldcourt Boats

Yacht alongside the pontoon at Oldcourt BoatsImage: Michael Harpur

The boatyard allows the odd ad-hoc stay alongside its barge and pontoon but if a vessel is left for any period an accommodation must be reached with the boatyard.

+353 (0) 21249,

+353 (0) 21249,  +353 (0)87 232 4151,

+353 (0)87 232 4151,  info@oldcourtboats.ie,

info@oldcourtboats.ie,  www.oldcourtboats.ie.

www.oldcourtboats.ie.How to get in?

Oldcourt 4½ miles above the entrance to the River Ilen

Oldcourt 4½ miles above the entrance to the River IlenImage: Michael Harpur

Offshore details are available in southwestern Ireland’s Coastal Overview for Cork Harbour to Mizen Head

Offshore details are available in southwestern Ireland’s Coastal Overview for Cork Harbour to Mizen Head  . The Harbour may be approached via its entrance from Long Island Bay or from the north end of Baltimore Harbour. The Baltimore North Entrance

. The Harbour may be approached via its entrance from Long Island Bay or from the north end of Baltimore Harbour. The Baltimore North Entrance  route provides a list of waypoints that assist pilotage through both the entrance to the River Ilen and the path from the north end of Baltimore Harbour.

route provides a list of waypoints that assist pilotage through both the entrance to the River Ilen and the path from the north end of Baltimore Harbour. The best time to access Oldcourt is three hours before high water. At the half tide, the path of the channel plus the smaller islands and rocks will be more evident. For any of the other lower river anchorages two hours before high water would be more than adequate. This timing also facilitates an approach to the river via Long Island Bay or The Sound on the early rising tide that will expose many of the rocks and dangers en route.

Boat approaching from Baltimore Harbour via The Sound

Boat approaching from Baltimore Harbour via The SoundImage: Michael Harpur

The preferred, most sheltered, and most frequented approach to the Ilen is through the relatively shallow Baltimore Harbour and out of its northern entrance via The Sound and into the river.

The preferred, most sheltered, and most frequented approach to the Ilen is through the relatively shallow Baltimore Harbour and out of its northern entrance via The Sound and into the river.  Yacht progressing up The Sound from Baltimore Harbour

Yacht progressing up The Sound from Baltimore HarbourImage: Burke Corbett

The Sound lies directly opposite the north entrance to Baltimore Harbour and is set in between Spanish Island and Sherkin Island. Keeping well clear of the Lousy and Wallis Rock surrounds, the least depth a vessel will encounter in the northern half of Baltimore Harbour whilst making way to The Sound is 2.5 metres LAT.

The Clear Island ferry passing out of The Sound passing under Turk Head

The Clear Island ferry passing out of The Sound passing under Turk HeadImage: Graham Rabbits

The Sound is straight and very deep, with at least 6.6 metres at its shallowest point, but it is not more than 150 metres wide at best. A southern approach to The Sound has been eased by the recent addition of the Narrow’s Ledge east cardinal buoy.

Narrow’s Ledge - East Cardinal Fl 3 15s position: 51° 29.345' N, 009° 23.832' W

Quarantine and Sandy islands at the north end of The Sound

Quarantine and Sandy islands at the north end of The SoundImage: Michael Harpur

The head of The Sound lies between Quarantine and Sandy islands where a listed waypoint is situated. It can be positively identified by Turk Head Quay on the north shore.

Turk Quay on the north shore

Turk Quay on the north shoreImage: Michael Harpur

The upriver path is to the east, or starboard, and the passage out to Long Island Bay is to the west, port. Take the starboard turn and follow the northeast tending river up towards Skibbereen as directed below.

Approaching the entrance from the south end of Long Island Bay

Approaching the entrance from the south end of Long Island BayImage: Burke Corbett

The river may also be entered and exited from the southern half of Long Island Bay, between Hare and Sherkin Islands. This approach twists and turns through narrow channels passing several undistinguished islets and islands. The channels have covered and exposed obstructions in the margins and the passage is particularly challenging at the entrance in the vicinity of Turk Head. This leaves zero margin for pilotage error so a good plotter, visibility and conditions will be essential for this cut. That said, in good conditions, it offers an interesting couple of hours of keen pilotage.

The river may also be entered and exited from the southern half of Long Island Bay, between Hare and Sherkin Islands. This approach twists and turns through narrow channels passing several undistinguished islets and islands. The channels have covered and exposed obstructions in the margins and the passage is particularly challenging at the entrance in the vicinity of Turk Head. This leaves zero margin for pilotage error so a good plotter, visibility and conditions will be essential for this cut. That said, in good conditions, it offers an interesting couple of hours of keen pilotage.  The entrance to the River Ilen

The entrance to the River IlenImage: Michael Harpur

The River Ilen Initial Fix is set on the rear clearing line of a bearing of 230°T of Doonanore Castle ruins open east of Illauneana, both on Clear Island with the latter 1½ miles northeast of the castle – as best seen on Admiralty 2129. Once in-line, track into the northwest of Sherkin on the reciprocal course of 050°T that leads towards the Sherkin Island side of the fairway. Staying on transit leads between Drowlaun Point, on Sherkin Islands northwest corner, and the outlying isolated Mullin Rock, with 2.1 metres of cover, located 500 metres to the northwest of the point.

The River Ilen Initial Fix is set on the rear clearing line of a bearing of 230°T of Doonanore Castle ruins open east of Illauneana, both on Clear Island with the latter 1½ miles northeast of the castle – as best seen on Admiralty 2129. Once in-line, track into the northwest of Sherkin on the reciprocal course of 050°T that leads towards the Sherkin Island side of the fairway. Staying on transit leads between Drowlaun Point, on Sherkin Islands northwest corner, and the outlying isolated Mullin Rock, with 2.1 metres of cover, located 500 metres to the northwest of the point.Mullin Rock - 2.1 metres of cover position: 009° 28.800' N, 051° 26.360' W

After passing between Hare Island and Sherkin Island, continue in for about a ½ mile and pick up a new astern clearing line on the alignment of about 212°T of Mount Lahan, at the north end of Clear Island, and Sherkin’s Drowlaun Point. This leads a vessel clear to the southeast of the unnamed dangerous rock off Hare Island, and well clear of Carrigoona that lies close off Sherkin Island.

Unnamed Rock off Hare Island – unmarked exposed rock position: 51° 29.372' N, 009° 25.375' W

_when_rounding_in.jpg) Stand off The Catalogues (right) when rounding in

Stand off The Catalogues (right) when rounding inImage: Burke Corbett

From here pass between Two Women's Rock and The Catalogues to where the River Ilen entrance opens. It is essential to stand well off The Catalogues Islands when rounding in as dangerous rocks extend northwestward from them.

The principal dangers in the mouth of the river are the Mealbeg Rocks, situated close south off Turk Head, and a drying rock that extends from the northeast-most point of Sandy Island. There is a usefull anchorage in the mouth of the river, to the north of the arch The Catalogues opposite Turk Head. This is a favourite mooring ground for small open boat fishermen who live on the north shore.

The river entrance opening around The Catalogues with Mealbeg buoy visible

The river entrance opening around The Catalogues with Mealbeg buoy visibleImage: Burke Corbett

The Mealbeg rocks are very much in the way of a vessel entering the River Ilen. These are two distinct rock groups of inner and outer rocks. The inner is a half-tide rock but the outer one is the real danger here as it is normally covered with its head only awash at low water. It is located about 50 metres to the south-southwest of the inner rock.

Outer Mealbeg - rock position: 51° 29.713' N, 009° 24.727' W

This is marked by a cardinal buoy moored close southeast.

Mealbeg – South Cardinal Buoy Fl 6 + LF1 15s position: 51° 29.704'N, 009° 24.721'W

Quarantine and Sandy islands within the entrance

Quarantine and Sandy islands within the entranceImage: Michael Harpur

The Sandy Island rock is well noted on charts and more of a concern for a vessel cutting the corner when entering or exiting The Sound. It lies close to the northeast point of the island and should be given a berth of 40 metres.

Sandy Island Rock – unmarked drying rock position: 51° 29.721' N, 009° 24.418' W

Shortly upriver then there is an anchorage available in the first reach within the deepwater above Quarantine Island

.

.  Inishleigh and Inane Point as seen from the west

Inishleigh and Inane Point as seen from the westImage: Michael Harpur

Continue upriver steering for Inane Point, on Ringarogy Island, then follow the channel as charted. Keep the Inane Point side of the fairway as a dangerous rock encroaches on the channel to the east of Inishleigh island that is marked by the Inishleigh cardinal buoy.

Inishleigh - South Cardinal 6 + LF1 15s position: 51° 30.050' N 009° 23.688' W

Above Inane Point, as is always the case with rivers and creeks, keep a sharp eye to the depth sounder all the way expecting the best water to be on the outside of bends. The next anchoring location is off Inane Quay

, about ¾ of a mile upriver from Inane Point. This is off an old quay where a modern house and pontoon will be seen overlooking the river.

, about ¾ of a mile upriver from Inane Point. This is off an old quay where a modern house and pontoon will be seen overlooking the river.  The anchorage of Inane Creek

The anchorage of Inane CreekImage: Michael Harpur

The Reena Dhuna

anchorage will be passed in the next reach to the northwest of the island of Inishbeg. It is located on a bend and at the top end of a northern length of the river before it turns east again. An old 19th-century slip and stone boathouse leading up to a fine 19th-century rectory will be seen on the north shore.

anchorage will be passed in the next reach to the northwest of the island of Inishbeg. It is located on a bend and at the top end of a northern length of the river before it turns east again. An old 19th-century slip and stone boathouse leading up to a fine 19th-century rectory will be seen on the north shore. Reena Dhuna anchorage

Reena Dhuna anchorageImage: Michael Harpur

Oldcourt is 1½ miles upriver, about 4 miles from the mouth and a mile to the northeast of the island of Inishbeg. Depths of 2 metres LAT or more will be found all the way up to the northeast corner of the Inishbeg. Then there is a shallow patch, with a charted depth of 0.8 metres, just off the northeast corner of Inishbeg, immediately after a slip is passed on the starboard side.

The reach to the north of Inishbeg

The reach to the north of InishbegImage: Michael Harpur

Hence vessels carrying any draft may require a supporting rise, that can amount to 3.5 metres, to proceed the last mile to Oldcourt. From here follow the river as it gently turns northeast for 400 metres and then turns east to reveal Oldcourt Boatyard alongside the ruins of a castle on the south side of the river.

The last leg of the run to Oldcourt from Inishbeg

The last leg of the run to Oldcourt from InishbegImage: Michael Harpur

Anchor according to your draft in the river taking care not to impede river traffic or boatyard operations. Alternatively, berth alongside a cement barge or the pontoon. This will be found up-river of the travel-lift dock and its 80 foot waiting pontoon that dries. At least two metres will be found alongside the barge at LWS.

Anchor according to your draft in the river taking care not to impede river traffic or boatyard operations. Alternatively, berth alongside a cement barge or the pontoon. This will be found up-river of the travel-lift dock and its 80 foot waiting pontoon that dries. At least two metres will be found alongside the barge at LWS.

Why visit here?

Formerly called Creagh Court, Creagh being the parish, it was first recorded as 'Auldecourte' in 1612. Oldcourt derives its name from the 'old court' of the castle that still overlooks the river from a southern rocky promontory to this day. The ruins of Oldcourt Castle and its castle

The ruins of Oldcourt Castle and its castle Image: Michael Harpur

The castle was built by the powerful 15th-century Gaelic O'Driscoll clan, see Baltimore Harbour, and in its medieval period probably stood on an island. The modest stronghold was most likely built to house a junior member of the leading family of the clan who would hold the fertile, low-lying surrounding lands. It was sited as near to the river as possible, which at high tide is almost directly below its entrance. This was to make the most of the river's ease of communications and its westward orientation directly overlooks the mudflats where the clan boats would have most likely moored. The 1612 name, 'Auldecourte', indicates that there must have been an enclosure or medieval bawn surrounded by buildings at the beginning of the 17th-century. When the O'Driscolls held power around Baltimore and its surrounding islands a fire signal lit on the top of their now fallen tower house at Ardagh would have been visible to the O'Driscoll occupants of Dunalong, Donegall (destroyed), Inispyke (destroyed) and Oldcourt. By this means the population of the Ilen river estuary would have valuable warning of suspect vessels.

The scant remains of Oldcourt Castle

The scant remains of Oldcourt Castle Image: Mike Searle via CC BY SA 2.0

Remarkably, the castle was still occupied by a senior member of the family, Denis O'Driscoll in the early part of the 18th-century. But by the middle of that century, the castle was in ruins and had been converted into a corn store. The entire Skibbereen corn harvest was exported by ship from the quay that had been by this stag built at the foot of the castle. Vessels capable of carrying 200 tons of grain moored here after been drawn upriver on the rise by small four-oared boats. Supported by the Oldcourt sea connection the town of Skibbereen grew to become became a regional hub of commerce. Skibbereen, in Irish An Sciobairín, and often shortened to Skibb, means 'little boat harbour'. Skibbereen’s town charter dates back to 1657 and a copy of this can be seen to this day in the town council chambers.

An Irish peasant family discovering the blight in their store

An Irish peasant family discovering the blight in their storeImage: Public Domain painting by Daniel MacDonald

This all came to a halt in the following century, during what would be Ireland’s darkest years 1846-49, when the Great Famine descended upon the country. The Great Famine, also called Irish Potato Famine, occurred when the potato crop failed in successive years. The crop failures were caused by late blight, a disease that destroys both the leaves and the edible roots, or tubers, of the potato plant. But the blight was more the catalyst for the disaster, as in truth the disaster had much deeper roots than that of a potato crop.

Searching for potatoes that survived the blight

Searching for potatoes that survived the blightImage: Public Domain

By the end of the 18th-century, Parliament began to slowly walk back the Penal Laws through a series of 'Catholic Relief Acts', but the damage was done. A system of shall holding tenant farmers and cottiers (labourers) was established that, especially in the west of Ireland, left holders struggling to both to provide for themselves and supply their landlords with enough produce to retain their holdings. Given the small size of the allotments and the various hardships that the land presented for farming crops, the local people had long since existed at a virtual subsistence level. Their survival was entirely dependent upon the potato which had become a staple crop in Ireland by the 18th century. But it was a subsistence level that had been driven down to fractions of an inch above the grave.

Frederick Douglass in the 1840s

Frederick Douglass in the 1840sImage: Public Domain

His time in Ireland exposed him to oppression which existed outside of America and it provided a new perspective and even deeper understanding for him on the issues faced at home. Although Douglass believed the conditions that the Irish lived in were worse than that of an American slave, he also made a clear distinction between the oppression of the Irish and the American slave. 'The Irish man is poor, but he is not a slave. He may be in rags, but he is not a slave. He is still the master of his body'.

The potatoes was a hardy, nutritious, and calorie-dense crop that was relatively easy to grow in Irish soil. It had become the backstop for the smallholders and cottiers whilst they provided the landlords with most everything else for rent that would be exported to Britain. The introduction of this crop and the need for farm labours led to a rapid period of population increase, around 1.6% per annum, in the first part of the 1800s. By 1841, the population had reached 8.2 million according to the census, but the actual figure is believed to be nearer 8.5 million and this was all based on the need to work the land and reliable nutrition the potatoes provided. So, when the potato crops suddenly failed and, worse, continued to do so, the floor finally fell out of the centuries-old system on Ireland's largest population.

Tenant Eviction

Tenant EvictionImage: Public Domain

Sadly, today it is accepted that there was plenty of food in Ireland to feed its starving citizens. But this continued to be exported by the largely absentee Anglo Irish landlord class who, far removed from events, ruthlessly pursued their commercial property investments through local agents and British authorities. When starving tenants could not pay their rents they soon started to lose money. Many began clearing the poor tenants from small plots and reletting the land in larger plots to bring in some returns to reduce their debts.

In 1846, there had been some clearances, but the great mass of evictions came in 1847 when no records were kept. A third of a million smallholdings disappeared and entire villages disappeared with them. It was only in 1849, when the Famine had largely passed, that the police began to keep a count. They recorded a total of almost 250,000 persons as officially been evicted in the following 5 years. It is estimated that 500,000 persons were evicted prior to this during the famine itself. Evicted families turned to live in ditches, at the heads of beaches or any unowned piece of wasteland. Bridget O'Donnel, the iconic drawing below, lived with the remains of her starving family under a bridge, but would not disclose the location to the artist for fear of being moved on. Society started to break down.

Evicted family surviving in a ditch during Black 47

Evicted family surviving in a ditch during Black 47Image: Public Domain

The peculiar ineffectiveness of the British Government to take action has many strands. Primarily the ruling British Whig administration of the time was adhering to a strict policy of laissez-faire, that the market would provide the food needed. But this entirely ignored the systemic food exports to England by the Anglo-Irish landlord classes. What also undermined resolve was a 19th-century Victorian belief that events, whether good or bad, had a place in God's divine plan. As such humankind could be relieved of need, blame or duty to intervene. This belief was a cornerstone of the justification for British imperialism and colonial expansion at the time. Hand in hand with this when Britain stood at the height of its imperial power there was a view that they were at the apex of the world social order. That the Irish ranked as one of the nation’s overseas subjects like any other. Moreover, the living conditions in Ireland, though largely driven by the British governance, and the Irish long since been depicted in Britain as lazy, drunk, and stupid could no more amplify these prejudices.

Depiction of Bridget O'Donnel a mother with a starving family

Depiction of Bridget O'Donnel a mother with a starving familyImage: Public Domain

So, to a large degree what undermined government action to effectively address the starving masses was a combination of a laissez-faire belief system, elitism, commercial interests as well as common prejudice and disdain for the Irish that was prevalent at the time. But it mattered not whether it was the potato, the Anglo Irish landlord class or the government that were to blame for the famine in Skibbereen, it was at its epicentre. By the end of what would be a sequence of Famines in Ireland, one in three of the population had either gone to the New World or to the other world. But for Skibbereen and its surroundings, one in three of its people were dead.

At its height, the people of Skibbereen were starving at such a rate that there were not enough alive to attend to the task of burying the dead. A kilometre east from the town, on the N71 to Schull near the ruins of the old Franciscan friary Abbeystrewery meaning 'Monastery of the Stream', a mass grave was dug to address the body count. Here an estimated 8,000 to 10,000 nameless, coffin-less victims were dumped into mass famine burial pits. As a reaction to the terror of the burial pits, many starving families resorted to taking their families to church graveyards. Here they would huddle in tight family groups and pass away together in the last hope that they might be buried in consecrated ground. All the while, the ships came upriver to the quay at Oldcourt, filled their hulls with produce and then set sail for England.

Starving people trying to secure a place in the workhouse

Starving people trying to secure a place in the workhouseImage: Public Domain

The town is appropriately and sadly renowned for carrying the title of a famous Great Famine song Skibbereen. The haunting melody carries the lyrics of a father recounting to his son the cruel reason why he left his beloved homeland in old Skibbereen. Both song and town stand today as hallmarks to the impact of the famine as well as the of the absentee landlords and the inappropriate British Government policy at the time. So hard hit, Skibbereen was selected to host a permanent famine exhibition located in the Skibbereen Heritage Centre, to commemorate this tragic period in Irish history. There is a particularly moving commemorative Famine trail that begins at the town centre that includes the Skibbereen Heritage Centre and the Abbeystrewery Cemetery. The Lough Hyne Visitor Centre is also situated in the Skibbereen Heritage Centre, as it is just 3km by road from Oldcourt. It hosts a permanent exhibition of the Lough that includes an audio-visual documentary on its history, formation and folklore. It also features a saltwater aquarium that houses examples of species from the Lough.

Depiction of one of the so called 'Coffin Ships' crossing the Atlantic

Depiction of one of the so called 'Coffin Ships' crossing the Atlantic Image: Public Domain

Today Skibbereen is once again a vibrant provincial town, and being the most southerly town in the country it acts as a district hub. It has a strong musical tradition and many different music events are held here each year. A few bars in town host various musical acts throughout the week. Oldcourt is just two miles short of the river’s main settlement and the area’s chief provincial town, so being the staging ground for a visit to Skibbereen is a prime reason to berth here. It is more than accessible by dinghy on a rising tide, and the town is only a 4km walk, or taxi ride, by a riverside road from Oldcourt.

Yacht anchored in the river above Oldcourt

Yacht anchored in the river above OldcourtImage: Graham Rabbits

From a boating perspective, Oldcourt provides the best River Ilen berthing opportunity. It is an ideal place to hide away in complete security upriver from any foul weather. Although alongside a busy boatyard, this is still a very quiet and rural environment with otters out of the water within view of the berth. It also holds the possibility of carrying out extensive maintenance at a choice of two of Ireland's most capable boatyards. Also, the town of Skibbereen and the services of a very good local family pub are all at hand.

What facilities are available?

Oldcourt boatyard offers complete facilties of boat building and workshop services. The boat hoist lifts vessels up to 70-ton in weight, or 21metres LOA with up to a 6 metre beam. Winter haul out and storage is also available. The owners of the boatyard are most accommodating and will watch over a boat if it needs to be left for an extended period. Hegarty's Boatyard also has a tracked slipway where a vessel may be winched out, plus a mobile crane. Outside of this Oldcourt is a quiet village with little more than a quiet family bar that does not serve food.The large provincial town of Skibbereen is a walk of 30 to 40 minutes away and well serviced by Bus Éireann. The town is the hub of west Cork and has all stores available plus one of the best chandleries in the southwest that has nearly everything a boatman could require.

Any security concerns?

Never an issue known to have occurred at Oldcourt.With thanks to:

Gareth Thomas, Yacht Jalfrezi.

Old Skibbereen

About Oldcourt

Formerly called Creagh Court, Creagh being the parish, it was first recorded as 'Auldecourte' in 1612. Oldcourt derives its name from the 'old court' of the castle that still overlooks the river from a southern rocky promontory to this day.

The ruins of Oldcourt Castle and its castle

The ruins of Oldcourt Castle and its castle Image: Michael Harpur

The castle was built by the powerful 15th-century Gaelic O'Driscoll clan, see Baltimore Harbour, and in its medieval period probably stood on an island. The modest stronghold was most likely built to house a junior member of the leading family of the clan who would hold the fertile, low-lying surrounding lands. It was sited as near to the river as possible, which at high tide is almost directly below its entrance. This was to make the most of the river's ease of communications and its westward orientation directly overlooks the mudflats where the clan boats would have most likely moored. The 1612 name, 'Auldecourte', indicates that there must have been an enclosure or medieval bawn surrounded by buildings at the beginning of the 17th-century. When the O'Driscolls held power around Baltimore and its surrounding islands a fire signal lit on the top of their now fallen tower house at Ardagh would have been visible to the O'Driscoll occupants of Dunalong, Donegall (destroyed), Inispyke (destroyed) and Oldcourt. By this means the population of the Ilen river estuary would have valuable warning of suspect vessels.

The scant remains of Oldcourt Castle

The scant remains of Oldcourt Castle Image: Mike Searle via CC BY SA 2.0

Remarkably, the castle was still occupied by a senior member of the family, Denis O'Driscoll in the early part of the 18th-century. But by the middle of that century, the castle was in ruins and had been converted into a corn store. The entire Skibbereen corn harvest was exported by ship from the quay that had been by this stag built at the foot of the castle. Vessels capable of carrying 200 tons of grain moored here after been drawn upriver on the rise by small four-oared boats. Supported by the Oldcourt sea connection the town of Skibbereen grew to become became a regional hub of commerce. Skibbereen, in Irish An Sciobairín, and often shortened to Skibb, means 'little boat harbour'. Skibbereen’s town charter dates back to 1657 and a copy of this can be seen to this day in the town council chambers.

An Irish peasant family discovering the blight in their store

An Irish peasant family discovering the blight in their storeImage: Public Domain painting by Daniel MacDonald

This all came to a halt in the following century, during what would be Ireland’s darkest years 1846-49, when the Great Famine descended upon the country. The Great Famine, also called Irish Potato Famine, occurred when the potato crop failed in successive years. The crop failures were caused by late blight, a disease that destroys both the leaves and the edible roots, or tubers, of the potato plant. But the blight was more the catalyst for the disaster, as in truth the disaster had much deeper roots than that of a potato crop.

Searching for potatoes that survived the blight

Searching for potatoes that survived the blightImage: Public Domain

By the end of the 18th-century, Parliament began to slowly walk back the Penal Laws through a series of 'Catholic Relief Acts', but the damage was done. A system of shall holding tenant farmers and cottiers (labourers) was established that, especially in the west of Ireland, left holders struggling to both to provide for themselves and supply their landlords with enough produce to retain their holdings. Given the small size of the allotments and the various hardships that the land presented for farming crops, the local people had long since existed at a virtual subsistence level. Their survival was entirely dependent upon the potato which had become a staple crop in Ireland by the 18th century. But it was a subsistence level that had been driven down to fractions of an inch above the grave.

Frederick Douglass in the 1840s

Frederick Douglass in the 1840sImage: Public Domain

His time in Ireland exposed him to oppression which existed outside of America and it provided a new perspective and even deeper understanding for him on the issues faced at home. Although Douglass believed the conditions that the Irish lived in were worse than that of an American slave, he also made a clear distinction between the oppression of the Irish and the American slave. 'The Irish man is poor, but he is not a slave. He may be in rags, but he is not a slave. He is still the master of his body'.

The potatoes was a hardy, nutritious, and calorie-dense crop that was relatively easy to grow in Irish soil. It had become the backstop for the smallholders and cottiers whilst they provided the landlords with most everything else for rent that would be exported to Britain. The introduction of this crop and the need for farm labours led to a rapid period of population increase, around 1.6% per annum, in the first part of the 1800s. By 1841, the population had reached 8.2 million according to the census, but the actual figure is believed to be nearer 8.5 million and this was all based on the need to work the land and reliable nutrition the potatoes provided. So, when the potato crops suddenly failed and, worse, continued to do so, the floor finally fell out of the centuries-old system on Ireland's largest population.

Tenant Eviction

Tenant EvictionImage: Public Domain

Sadly, today it is accepted that there was plenty of food in Ireland to feed its starving citizens. But this continued to be exported by the largely absentee Anglo Irish landlord class who, far removed from events, ruthlessly pursued their commercial property investments through local agents and British authorities. When starving tenants could not pay their rents they soon started to lose money. Many began clearing the poor tenants from small plots and reletting the land in larger plots to bring in some returns to reduce their debts.

In 1846, there had been some clearances, but the great mass of evictions came in 1847 when no records were kept. A third of a million smallholdings disappeared and entire villages disappeared with them. It was only in 1849, when the Famine had largely passed, that the police began to keep a count. They recorded a total of almost 250,000 persons as officially been evicted in the following 5 years. It is estimated that 500,000 persons were evicted prior to this during the famine itself. Evicted families turned to live in ditches, at the heads of beaches or any unowned piece of wasteland. Bridget O'Donnel, the iconic drawing below, lived with the remains of her starving family under a bridge, but would not disclose the location to the artist for fear of being moved on. Society started to break down.

Evicted family surviving in a ditch during Black 47

Evicted family surviving in a ditch during Black 47Image: Public Domain

The peculiar ineffectiveness of the British Government to take action has many strands. Primarily the ruling British Whig administration of the time was adhering to a strict policy of laissez-faire, that the market would provide the food needed. But this entirely ignored the systemic food exports to England by the Anglo-Irish landlord classes. What also undermined resolve was a 19th-century Victorian belief that events, whether good or bad, had a place in God's divine plan. As such humankind could be relieved of need, blame or duty to intervene. This belief was a cornerstone of the justification for British imperialism and colonial expansion at the time. Hand in hand with this when Britain stood at the height of its imperial power there was a view that they were at the apex of the world social order. That the Irish ranked as one of the nation’s overseas subjects like any other. Moreover, the living conditions in Ireland, though largely driven by the British governance, and the Irish long since been depicted in Britain as lazy, drunk, and stupid could no more amplify these prejudices.

Depiction of Bridget O'Donnel a mother with a starving family

Depiction of Bridget O'Donnel a mother with a starving familyImage: Public Domain

So, to a large degree what undermined government action to effectively address the starving masses was a combination of a laissez-faire belief system, elitism, commercial interests as well as common prejudice and disdain for the Irish that was prevalent at the time. But it mattered not whether it was the potato, the Anglo Irish landlord class or the government that were to blame for the famine in Skibbereen, it was at its epicentre. By the end of what would be a sequence of Famines in Ireland, one in three of the population had either gone to the New World or to the other world. But for Skibbereen and its surroundings, one in three of its people were dead.

At its height, the people of Skibbereen were starving at such a rate that there were not enough alive to attend to the task of burying the dead. A kilometre east from the town, on the N71 to Schull near the ruins of the old Franciscan friary Abbeystrewery meaning 'Monastery of the Stream', a mass grave was dug to address the body count. Here an estimated 8,000 to 10,000 nameless, coffin-less victims were dumped into mass famine burial pits. As a reaction to the terror of the burial pits, many starving families resorted to taking their families to church graveyards. Here they would huddle in tight family groups and pass away together in the last hope that they might be buried in consecrated ground. All the while, the ships came upriver to the quay at Oldcourt, filled their hulls with produce and then set sail for England.

Starving people trying to secure a place in the workhouse

Starving people trying to secure a place in the workhouseImage: Public Domain

The town is appropriately and sadly renowned for carrying the title of a famous Great Famine song Skibbereen. The haunting melody carries the lyrics of a father recounting to his son the cruel reason why he left his beloved homeland in old Skibbereen. Both song and town stand today as hallmarks to the impact of the famine as well as the of the absentee landlords and the inappropriate British Government policy at the time. So hard hit, Skibbereen was selected to host a permanent famine exhibition located in the Skibbereen Heritage Centre, to commemorate this tragic period in Irish history. There is a particularly moving commemorative Famine trail that begins at the town centre that includes the Skibbereen Heritage Centre and the Abbeystrewery Cemetery. The Lough Hyne Visitor Centre is also situated in the Skibbereen Heritage Centre, as it is just 3km by road from Oldcourt. It hosts a permanent exhibition of the Lough that includes an audio-visual documentary on its history, formation and folklore. It also features a saltwater aquarium that houses examples of species from the Lough.

Depiction of one of the so called 'Coffin Ships' crossing the Atlantic

Depiction of one of the so called 'Coffin Ships' crossing the Atlantic Image: Public Domain

Today Skibbereen is once again a vibrant provincial town, and being the most southerly town in the country it acts as a district hub. It has a strong musical tradition and many different music events are held here each year. A few bars in town host various musical acts throughout the week. Oldcourt is just two miles short of the river’s main settlement and the area’s chief provincial town, so being the staging ground for a visit to Skibbereen is a prime reason to berth here. It is more than accessible by dinghy on a rising tide, and the town is only a 4km walk, or taxi ride, by a riverside road from Oldcourt.

Yacht anchored in the river above Oldcourt

Yacht anchored in the river above OldcourtImage: Graham Rabbits

From a boating perspective, Oldcourt provides the best River Ilen berthing opportunity. It is an ideal place to hide away in complete security upriver from any foul weather. Although alongside a busy boatyard, this is still a very quiet and rural environment with otters out of the water within view of the berth. It also holds the possibility of carrying out extensive maintenance at a choice of two of Ireland's most capable boatyards. Also, the town of Skibbereen and the services of a very good local family pub are all at hand.

Other options in this area

Click the 'Next' and 'Previous' buttons to progress through neighbouring havens in a coastal 'clockwise' or 'anti-clockwise' sequence. Alternatively here are the ten nearest havens available in picture view:

Coastal clockwise:

Reena Dhuna - 1.2 miles WSWTurk Head - 2.6 miles SW

Rincolisky Harbour - 2.7 miles WSW

East Pier - 2.6 miles WSW

Trá Bán - 2.8 miles WSW

Coastal anti-clockwise:

Inane Creek - 1.6 miles SWQuarantine Island - 2.4 miles SW

Kinish Harbour - 3.1 miles SW

North Harbour (Trawkieran) - 5.5 miles SW

South Harbour (Ineer) - 5.7 miles SW

Navigational pictures

These additional images feature in the 'How to get in' section of our detailed view for Oldcourt.

_when_rounding_in.jpg)

| Detail view | Off |

| Picture view | On |

Old Skibbereen

Add your review or comment:

Please log in to leave a review of this haven.

Please note eOceanic makes no guarantee of the validity of this information, we have not visited this haven and do not have first-hand experience to qualify the data. Although the contributors are vetted by peer review as practised authorities, they are in no way, whatsoever, responsible for the accuracy of their contributions. It is essential that you thoroughly check the accuracy and suitability for your vessel of any waypoints offered in any context plus the precision of your GPS. Any data provided on this page is entirely used at your own risk and you must read our legal page if you view data on this site. Free to use sea charts courtesy of Navionics.