Mill Cove is a tiny sea inlet on the southwest coast of Ireland, about two miles east of Glandore and three and a half miles northwest of Galley Head. It offers a secluded anchorage off a small quay about halfway up the inlet.

The inlet provides an exposed anchorage that can be used in northerly components or offshore winds and it is entirely open to anything from south. Daylight access is required to find the unmarked inlet and the passage through the rocks that are situated on either side of the entrance.

Keyfacts for Mill Cove

Last modified

September 24th 2021 Summary

A tolerable location with attentive navigation required for access.Facilities

Nature

Considerations

Position and approaches

Expand to new tab or fullscreen

Haven position

51° 33.392' N, 009° 2.578' W

51° 33.392' N, 009° 2.578' WThis is in the middle of the cove near the head of the quay.

What is the initial fix?

The following Mill Cove initial fix will set up a final approach:

51° 32.836' N, 009° 2.439' W

51° 32.836' N, 009° 2.439' W What are the key points of the approach?

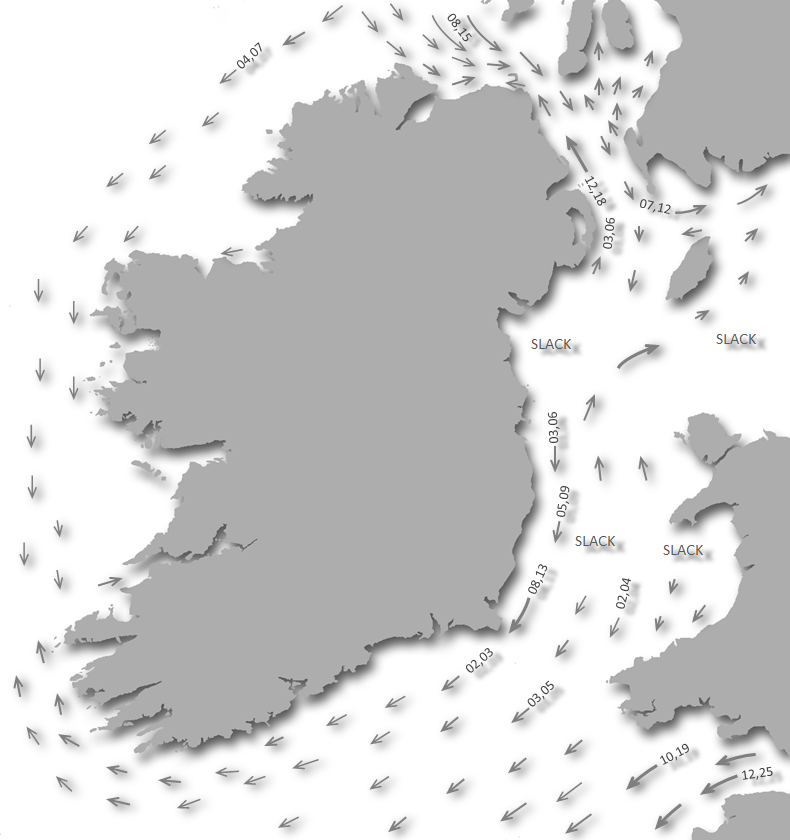

Offshore details are available in southwestern Ireland’s Coastal Overview for Cork Harbour to Mizen Head  .

.

.

. - Keeping at least a ⅓ of a mile offshore until the bay is identified.

- Pass in steering northward between rocks on both side that flank the approach.

Not what you need?

Click the 'Next' and 'Previous' buttons to progress through neighbouring havens in a coastal 'clockwise' or 'anti-clockwise' sequence. Below are the ten nearest havens to Mill Cove for your convenience.

Ten nearest havens by straight line charted distance and bearing:

- Tralong Bay - 0.7 nautical miles WSW

- Rosscarbery Inlet - 1.2 nautical miles ENE

- Glandore - 3.1 nautical miles W

- Rabbit Island Sound - 3.3 nautical miles WSW

- Squince Harbour - 3.6 nautical miles WSW

- Dirk Bay - 3.9 nautical miles ESE

- Blind Harbour - 4.6 nautical miles WSW

- Castlehaven (Castletownshend) - 5.1 nautical miles WSW

- Dunnycove Bay - 5.7 nautical miles E

- Clonakilty Harbour (Ring) - 7.8 nautical miles ENE

These havens are ordered by straight line charted distance and bearing, and can be reordered by compass direction or coastal sequence:

- Tralong Bay - 0.7 miles WSW

- Rosscarbery Inlet - 1.2 miles ENE

- Glandore - 3.1 miles W

- Rabbit Island Sound - 3.3 miles WSW

- Squince Harbour - 3.6 miles WSW

- Dirk Bay - 3.9 miles ESE

- Blind Harbour - 4.6 miles WSW

- Castlehaven (Castletownshend) - 5.1 miles WSW

- Dunnycove Bay - 5.7 miles E

- Clonakilty Harbour (Ring) - 7.8 miles ENE

What's the story here?

Mill Cove with Galley Head seen in the backdrop

Mill Cove with Galley Head seen in the backdropImage: Michael Harpur

Mill Cove is a narrow inlet situated on Glandore Bay less than a mile east of Tralong Bay and about midway between Glandore and the Rosscarbery inlet. It is a small naturally sheltered sea inlet where the Ballyvireen flows into the sea. A stone quay lies on its eastern side that attracts some visitors in the summer months and a small scattering of houses are situated around it.

Houses and slips at the root of Mill Cove's pier

Houses and slips at the root of Mill Cove's pierImage: Michael Harpur

In offshore winds, the bay offers an anchorage to small yacht southwest of a pier within the inlet. 3 metres will be found in the neck of the entrance and this shallows 1.5 metres to the southwest of the quay and less beyond. Mill Cove is only suited to shallow draught craft, and its neighbour Tralong Bay is a better option for deep keeled yachts with more swing room.

How to get in?

_seen_over_the_entrance_to_mill_cove.jpg) Galley Head (3½ miles distance) seen over the entrance to Mill Cove

Galley Head (3½ miles distance) seen over the entrance to Mill CoveImage: Michael Harpur

Use Ireland’s coastal overview for Cork Harbour to Mizen Head

Use Ireland’s coastal overview for Cork Harbour to Mizen Head  for seaward approaches. Glandore Bay lies between Sheela Point and Galley Head, a distance of about 5¾ miles, and embraces Glandore Harbour, Rosscarbery Bay and some small inlets, of which Mill Cove is one. The Glandore

for seaward approaches. Glandore Bay lies between Sheela Point and Galley Head, a distance of about 5¾ miles, and embraces Glandore Harbour, Rosscarbery Bay and some small inlets, of which Mill Cove is one. The Glandore  entry provides approach directions for this general area although from seaward Mill Cove can be difficult to identify for first-time visitors.

entry provides approach directions for this general area although from seaward Mill Cove can be difficult to identify for first-time visitors. Tralong Bay, behind Black Rock, and Mill Cove Right as seen from seaward

Tralong Bay, behind Black Rock, and Mill Cove Right as seen from seawardImage: Burke Corbett

Vessels approaching from the west, or Glandore area, will readily identify Mill Cove by following the shoreline past Tralong Bay, situated a mile from Goats Head, and the entrance to Mill Cove a further ½ mile eastward. Keeping 500 metres off the shoreline from Glandore clears all dangers.

_.jpg) The ruin of Downeen Castle overlooking Castle Bay (as seen from the northeast)

The ruin of Downeen Castle overlooking Castle Bay (as seen from the northeast) Image: Mike Searle via CC BY SA 2.0

Vessels approaching from the east will find it slightly more difficult to identify. The inlet has few if any distinctive marks from seaward. Likewise several of Castle Bay's recesses, situated immediately east, give the impression of being an inlet from seaward.

Castle Bay as seen on the approach to Mill Cove

Castle Bay as seen on the approach to Mill CoveImage: Burke Corbett

A good set of marks for the adjacent Castle Bay is the ruin of Downeen Castle that stands as a solitary figure on a pinnacle of rock on its eastern extremity. Inshore of this are the ruins of Tower Downeen Castle or North Downeen Castle, situated a ⅓ of a mile north by northeast on the skyline, plus a large red-roofed farm shed. Mill Cove is situated ¾ of a mile to the southwest of Downeen Castle round the headland that marks the southwestern extremity of Castle Bay. Keeping Castle Bay to the east, which has a few more identifiable features, assists in placing Mill Cove.

Mill Cove starting to open from seaward

Mill Cove starting to open from seawardImage: Burke Corbett

From the initial fix, the small, very narrow, southeast-facing Mill Cove will become apparent. It will be seen at the head of an approach that funnels in between rocks on either side.

From the initial fix, the small, very narrow, southeast-facing Mill Cove will become apparent. It will be seen at the head of an approach that funnels in between rocks on either side.  The drying Black Rocks on the western side of the approach

The drying Black Rocks on the western side of the approachImage: Burke Corbett

The most conspicuous are the Black Rocks on the western side of the approach to the inlet are the most prominent. They form a drying cluster and extend nearly 400 metres offshore with foul ground within.

Outlier of the eastern headland awash

Outlier of the eastern headland awashImage: Burke Corbett

Covered rocks also extend 200 metres off the eastern headland, between Mill Cove and Castle Bay. The space between these outer rocks is ⅓ of a mile wide so there is plenty of sea room.

Mill Cove open for the final approach

Mill Cove open for the final approachImage: Burke Corbett

The inlet itself is very narrow and depths decrease very quickly after the western headland is passed to port. 200 metres beyond it and depths descend to 5 metres LAT, then to 2 metres LAT 200 further in.

The inlet itself is very narrow and depths decrease very quickly after the western headland is passed to port. 200 metres beyond it and depths descend to 5 metres LAT, then to 2 metres LAT 200 further in.  The run up the inlet to the stone Quay

The run up the inlet to the stone QuayImage: Michael Harpur

The small stone quay will be seen in the northeast corner and to shallows to 1.5 metres to the southwest of the quay and less beyond. The head of the inlet is almost entirely taken up with small-boat moorings.

Mill Cove as seen from the anchoring area

Mill Cove as seen from the anchoring areaImage: Burke Corbett

Anchor in sand according to draft and conditions. Land at the quay by dinghy or on the slip on the opposite shore.

Why visit here?

It is uncertain how Mill Cove got its name. Possibly because the steeply shelving sides of the Roury valley once had a watermill that has long since disappeared. The stream itself is said to derive its name from O'Ruaidhre, a follower of a chieftain named O'Leary, who lived formerly in this area but fled to Macroom after the Norman invasion.About 700 metres further upstream and overlooking from its banks, in the townland of Ballyvoreen, stand the ruins Coppinger's Court or Coppinger's Folly. Named after the notorious Cork merchant and moneylender Sir Walter Coppinger he built the strong house between the 1620s and 30s. Sir Walter acquired the valley and surrounding lands from the previous owner, Fineen O'Driscoll, by foreclosing on a mortgage after advancing him a sum of money. His grand designs were to widening and deepening the stream so a canal could be built to service a small inland harbour at the foot of his castle. From this a market-town, he would build, would flourish.

The steeply shelving sides of the Roury valley would have lent themselves to a

The steeply shelving sides of the Roury valley would have lent themselves to amill

Image: Michael Harpur

No details were left to chance for his great sea-port town and meticulous plans were made for the layout of townhouses, wharves, connecting roads and so forth with his project commencing with complete castle rebuild. Local labour was so 'cheap' at the time that the limestones for his castle were not carted but passed the two miles from the quarry to the site along a human chain (hand to hand). The completed castle was a thing of local marvel 'having a chimney for every month of the year, and a door for every week of the year'. Coppinger would never live to see his great seaport however as he died in 1639 and is buried in Christ Church, Cork. His surviving plans for a seaport came to an abrupt end when two years after he had passed the stronghold was attacked during the Irish Rebellion of 1641 and badly damaged by fire. Despite having a number of sons, Sir Walter's brother, Dominic, took possession of his property. It was never restored and fell into ruins over the following years.

Coppingers Court

Coppingers CourtImage: Mike Searle via CC BY SA 2.0

The cove's most notable features are its old Coastguard cottages and pier. These are part of a ring of similar installations built at intervals of about ten to twenty miles around the coast of Ireland in the 19th-century. You would be forgiven for thinking that these structures were set in place for the preservation of life much the same as the RNLI today. But this was very far from the case and the stations correctly described in their time as Coast Guard service. Their singular objective was the protection of tax revenue for the Exchequer so as to pay for the many wars and global expansion of the period. Up until 1841, when Prime Minister Robert Peel killed off most of the benefits of smuggling by eliminating tariffs on more than 600 products, there was a lot of money to be made in this rough trade.

The ruin of Coppingers Court

The ruin of Coppingers CourtImage: Mike Searle via CC BY SA 2.0

The men who manned these buildings were a close-knit group of mostly ex-naval men, that would have shared a sense of, discipline, camaraderie and empire. And they only had themselves to count upon as most often the remote locations of the stations, such as Mill Cove, they were apart from the local community who often viewed with suspicion and especially those with smuggling sympathies. It was intended the units should keep themselves apart as wily local smugglers would attempt to get lonesome local Coast Guards to marry their daughters so they would turn a blind eye to their activities. To counter this the men were moved on every few years to help maintain their separation from the local community. This rotation is believed to be the origin, of what was then a caveat, 'every nice girl loves a sailor'. But there was also the possibilities of large amounts of prize money being won. And the case of John Dillon the then commander of Preventive Coast Guard at Mill Bay must have been told through the long nights of these stations nationally.

Mill Cove has formed itself around its 18th-century Coastguard station

Mill Cove has formed itself around its 18th-century Coastguard stationImage: Michael Harpur

Hansard's Parliamentary Debates of 1839 noted the case… 'Mr. Dillon, the petitioner had been nine years a master mariner in the royal navy and had afterwards served in the coast guard, in a situation which required good seamanship, much courage, and a great deal of judgment, skill, and discretion. It appeared, that he had performed all the duties of this situation with ability, skill, and courage, that he did not omit anything that zeal could prompt, or that courage guided by prudence could achieve.

The stone pier of the Coast Guard station

The stone pier of the Coast Guard stationImage: Michael Harpur

John was very much as described out in his boat on duty with his crew of four looking for a rumoured American smuggler brig that was off the coast attempting to land a cargo of tobacco. A short time after nightfall, he observed a sail bearing down towards Mill Cove making for the harbour of Glandore. Dillon approached and hailed the vessel that refused to lie too made him believed he had come upon the expected smuggler. Conditions were rough and Dillon could not attempt to board the brig who had hastily put about, and, made out for sea. Dillon pursued, just about keeping up with and firing on her. He lost sight of the brig after she had rounded the Old Head of Kinsale and presuming that they had cleared the Head and got off to sea, he decided to break off the pursuit should his small boat with four men be overwhelmed by a heavy sea running off the head. So he put back to Mill Cove, satisfied that he had prevented a landing by beating the vessel of that part of the coast. Unbeknown to him the brig, however, became embayed, and with a gale building, decided to put into the harbour of Kinsale.

The old stone quay retains its original stone bollards

The old stone quay retains its original stone bollards Image: Michael Harpur

Hansard's Parliamentary Debates takes up the account.. Mr. Dillon having the command of a boat engaged in the coast-guard service at Mill Cove Harbour, in the county of Cork, surprised and chased a smuggler of very superior size, crowded with men and well armed, drove her from Mill Cove Harbour, where she evidently intended to make a landing, and compelled her, by the closeness of his pursuit, to seek for refuge in the harbour of Kinsale, where she was captured, and ultimately condemned. Immediately after the transaction, Mr Dillon received a letter from the Treasury, expressing the highest approbation of his conduct, but much litigation ensued before the smuggler was finally condemned.'

The Coast Guard building overlooking the anchorage today

The Coast Guard building overlooking the anchorage today Image: Burke Corbett

But the receipt of his prize was not to be as the court case had to be settled first and Mr. Dillon entered the merchant service and sailed to the West Indies, where he remained for upwards of four years. He watched the Gazette to await the notification of condemnation by the court where he could then claim his prize as by an Act of Parliament, it was required that the names of all vessels condemned should be published in the Gazette. But as it happens… Whether from accident or not he knew not; but that form, in the present instance, was omitted, and the consequence was, that Mr Dillon was not aware of the condemnation of the vessel till his return. Worse he found out that the Kinsale Mr Masters received £11,786 as his share as seizing officer, whilst Mr Dillon, the bona fide (if the matter be equitably considered) captor, got but £50. It was quite clear, that if anybody had a title to that sum, it was Mr Dillon. He accordingly made his claim; and then, for the first time, he heard that there had been a charge made against him of cowardice for not boarding the vessel.

The slipway opposite the pier leading the western side of the cove

The slipway opposite the pier leading the western side of the coveImage: Burke Corbett

So not only had he prevented the vessel from landing its £53,000 of tobacco, and chasing her into a situation in which she could not avoid being captured, only losing sight of her for a brief period towards the conclusion of the chase, he not only did not receive his just share of the prize money, he also lost his standing as a commander. After making a determined stand which has cost him nearly £5,000 he was fully and honourably acquitted of cowardice and only ever received the £51. Doubtlessly a story that would have been told and retold by the nineteenth-century coastguards throughout the land.

Mill Cove in its rural picturesque West Cork setting as seen from the west

Mill Cove in its rural picturesque West Cork setting as seen from the westImage: Michael Harpur

The remains of Coppinger’s Elizabethan style house can be seen in Ballyvireen today. The remains spark the imagination of the project for Mill Cove and Ballyvireen, and are well worth a short excursion up the valley to explore them. Any walk here will provide wonderful visits over this picturesque part of West Cork.

The view to seaward from the anchoring area

The view to seaward from the anchoring areaImage: Burke Corbett

From a boating perspective, this a beautiful little cove and another settled weather berthing opportunity on this scenic coastline, albeit ideally only for shallower draft boats to make the best of it.

What facilities are available?

Water is available at the quay and a slip, but there are no other facilities at this location.Any security concerns?

Never an issue known to have occurred to a vessel at Mill Cove.With thanks to:

Burke Corbett, Gusserane, New Ross, Co. Wexford. Photography with thanks to Burke Corbett and Mike Searle.About Mill Cove

It is uncertain how Mill Cove got its name. Possibly because the steeply shelving sides of the Roury valley once had a watermill that has long since disappeared. The stream itself is said to derive its name from O'Ruaidhre, a follower of a chieftain named O'Leary, who lived formerly in this area but fled to Macroom after the Norman invasion.

About 700 metres further upstream and overlooking from its banks, in the townland of Ballyvoreen, stand the ruins Coppinger's Court or Coppinger's Folly. Named after the notorious Cork merchant and moneylender Sir Walter Coppinger he built the strong house between the 1620s and 30s. Sir Walter acquired the valley and surrounding lands from the previous owner, Fineen O'Driscoll, by foreclosing on a mortgage after advancing him a sum of money. His grand designs were to widening and deepening the stream so a canal could be built to service a small inland harbour at the foot of his castle. From this a market-town, he would build, would flourish.

The steeply shelving sides of the Roury valley would have lent themselves to a

The steeply shelving sides of the Roury valley would have lent themselves to amill

Image: Michael Harpur

No details were left to chance for his great sea-port town and meticulous plans were made for the layout of townhouses, wharves, connecting roads and so forth with his project commencing with complete castle rebuild. Local labour was so 'cheap' at the time that the limestones for his castle were not carted but passed the two miles from the quarry to the site along a human chain (hand to hand). The completed castle was a thing of local marvel 'having a chimney for every month of the year, and a door for every week of the year'. Coppinger would never live to see his great seaport however as he died in 1639 and is buried in Christ Church, Cork. His surviving plans for a seaport came to an abrupt end when two years after he had passed the stronghold was attacked during the Irish Rebellion of 1641 and badly damaged by fire. Despite having a number of sons, Sir Walter's brother, Dominic, took possession of his property. It was never restored and fell into ruins over the following years.

Coppingers Court

Coppingers CourtImage: Mike Searle via CC BY SA 2.0

The cove's most notable features are its old Coastguard cottages and pier. These are part of a ring of similar installations built at intervals of about ten to twenty miles around the coast of Ireland in the 19th-century. You would be forgiven for thinking that these structures were set in place for the preservation of life much the same as the RNLI today. But this was very far from the case and the stations correctly described in their time as Coast Guard service. Their singular objective was the protection of tax revenue for the Exchequer so as to pay for the many wars and global expansion of the period. Up until 1841, when Prime Minister Robert Peel killed off most of the benefits of smuggling by eliminating tariffs on more than 600 products, there was a lot of money to be made in this rough trade.

The ruin of Coppingers Court

The ruin of Coppingers CourtImage: Mike Searle via CC BY SA 2.0

The men who manned these buildings were a close-knit group of mostly ex-naval men, that would have shared a sense of, discipline, camaraderie and empire. And they only had themselves to count upon as most often the remote locations of the stations, such as Mill Cove, they were apart from the local community who often viewed with suspicion and especially those with smuggling sympathies. It was intended the units should keep themselves apart as wily local smugglers would attempt to get lonesome local Coast Guards to marry their daughters so they would turn a blind eye to their activities. To counter this the men were moved on every few years to help maintain their separation from the local community. This rotation is believed to be the origin, of what was then a caveat, 'every nice girl loves a sailor'. But there was also the possibilities of large amounts of prize money being won. And the case of John Dillon the then commander of Preventive Coast Guard at Mill Bay must have been told through the long nights of these stations nationally.

Mill Cove has formed itself around its 18th-century Coastguard station

Mill Cove has formed itself around its 18th-century Coastguard stationImage: Michael Harpur

Hansard's Parliamentary Debates of 1839 noted the case… 'Mr. Dillon, the petitioner had been nine years a master mariner in the royal navy and had afterwards served in the coast guard, in a situation which required good seamanship, much courage, and a great deal of judgment, skill, and discretion. It appeared, that he had performed all the duties of this situation with ability, skill, and courage, that he did not omit anything that zeal could prompt, or that courage guided by prudence could achieve.

The stone pier of the Coast Guard station

The stone pier of the Coast Guard stationImage: Michael Harpur

John was very much as described out in his boat on duty with his crew of four looking for a rumoured American smuggler brig that was off the coast attempting to land a cargo of tobacco. A short time after nightfall, he observed a sail bearing down towards Mill Cove making for the harbour of Glandore. Dillon approached and hailed the vessel that refused to lie too made him believed he had come upon the expected smuggler. Conditions were rough and Dillon could not attempt to board the brig who had hastily put about, and, made out for sea. Dillon pursued, just about keeping up with and firing on her. He lost sight of the brig after she had rounded the Old Head of Kinsale and presuming that they had cleared the Head and got off to sea, he decided to break off the pursuit should his small boat with four men be overwhelmed by a heavy sea running off the head. So he put back to Mill Cove, satisfied that he had prevented a landing by beating the vessel of that part of the coast. Unbeknown to him the brig, however, became embayed, and with a gale building, decided to put into the harbour of Kinsale.

The old stone quay retains its original stone bollards

The old stone quay retains its original stone bollards Image: Michael Harpur

Hansard's Parliamentary Debates takes up the account.. Mr. Dillon having the command of a boat engaged in the coast-guard service at Mill Cove Harbour, in the county of Cork, surprised and chased a smuggler of very superior size, crowded with men and well armed, drove her from Mill Cove Harbour, where she evidently intended to make a landing, and compelled her, by the closeness of his pursuit, to seek for refuge in the harbour of Kinsale, where she was captured, and ultimately condemned. Immediately after the transaction, Mr Dillon received a letter from the Treasury, expressing the highest approbation of his conduct, but much litigation ensued before the smuggler was finally condemned.'

The Coast Guard building overlooking the anchorage today

The Coast Guard building overlooking the anchorage today Image: Burke Corbett

But the receipt of his prize was not to be as the court case had to be settled first and Mr. Dillon entered the merchant service and sailed to the West Indies, where he remained for upwards of four years. He watched the Gazette to await the notification of condemnation by the court where he could then claim his prize as by an Act of Parliament, it was required that the names of all vessels condemned should be published in the Gazette. But as it happens… Whether from accident or not he knew not; but that form, in the present instance, was omitted, and the consequence was, that Mr Dillon was not aware of the condemnation of the vessel till his return. Worse he found out that the Kinsale Mr Masters received £11,786 as his share as seizing officer, whilst Mr Dillon, the bona fide (if the matter be equitably considered) captor, got but £50. It was quite clear, that if anybody had a title to that sum, it was Mr Dillon. He accordingly made his claim; and then, for the first time, he heard that there had been a charge made against him of cowardice for not boarding the vessel.

The slipway opposite the pier leading the western side of the cove

The slipway opposite the pier leading the western side of the coveImage: Burke Corbett

So not only had he prevented the vessel from landing its £53,000 of tobacco, and chasing her into a situation in which she could not avoid being captured, only losing sight of her for a brief period towards the conclusion of the chase, he not only did not receive his just share of the prize money, he also lost his standing as a commander. After making a determined stand which has cost him nearly £5,000 he was fully and honourably acquitted of cowardice and only ever received the £51. Doubtlessly a story that would have been told and retold by the nineteenth-century coastguards throughout the land.

Mill Cove in its rural picturesque West Cork setting as seen from the west

Mill Cove in its rural picturesque West Cork setting as seen from the westImage: Michael Harpur

The remains of Coppinger’s Elizabethan style house can be seen in Ballyvireen today. The remains spark the imagination of the project for Mill Cove and Ballyvireen, and are well worth a short excursion up the valley to explore them. Any walk here will provide wonderful visits over this picturesque part of West Cork.

The view to seaward from the anchoring area

The view to seaward from the anchoring areaImage: Burke Corbett

From a boating perspective, this a beautiful little cove and another settled weather berthing opportunity on this scenic coastline, albeit ideally only for shallower draft boats to make the best of it.

Other options in this area

Click the 'Next' and 'Previous' buttons to progress through neighbouring havens in a coastal 'clockwise' or 'anti-clockwise' sequence. Alternatively here are the ten nearest havens available in picture view:

Coastal clockwise:

Tralong Bay - 0.4 miles WSWGlandore - 1.9 miles W

Rabbit Island Sound - 2 miles WSW

Squince Harbour - 2.2 miles WSW

Blind Harbour - 2.9 miles WSW

Coastal anti-clockwise:

Rosscarbery Inlet - 0.8 miles ENEDirk Bay - 2.4 miles ESE

Dunnycove Bay - 3.5 miles E

Clonakilty Harbour (Ring) - 4.8 miles ENE

Dunworly Bay - 6.6 miles E

Navigational pictures

These additional images feature in the 'How to get in' section of our detailed view for Mill Cove.

_seen_over_the_entrance_to_mill_cove.jpg)

_.jpg)

| Detail view | Off |

| Picture view | On |

Add your review or comment:

Please log in to leave a review of this haven.

Please note eOceanic makes no guarantee of the validity of this information, we have not visited this haven and do not have first-hand experience to qualify the data. Although the contributors are vetted by peer review as practised authorities, they are in no way, whatsoever, responsible for the accuracy of their contributions. It is essential that you thoroughly check the accuracy and suitability for your vessel of any waypoints offered in any context plus the precision of your GPS. Any data provided on this page is entirely used at your own risk and you must read our legal page if you view data on this site. Free to use sea charts courtesy of Navionics.