Bannow Bay is located on the southeast coast of Ireland, on the east side of the Hook Peninsula and 7 miles northeast of Hook Head Lighthouse. The bay offers an anchorage in a secluded rural setting. With detailed planning and the benefit of local boating knowledge, it could also be possible for a shallow-draught vessel to enter an extensive tidal inlet that connects to the head of the bay.

The bay affords a vessel good protection from the west through north to northeast.

Shallow-draught vessels can find complete protection inside the tidal inlet, but this is not freely accessible. It requires a good weather window, advice and careful deliberation. Access to the outer anchorage is straightforward as, save for an easily avoided, well-covered rock, the approach path is clear.

Keyfacts for Bannow Bay

Last modified

May 20th 2022 Summary

A good location with straightforward access.Facilities

Nature

Considerations

Position and approaches

Expand to new tab or fullscreen

Haven position

52° 12.158' N, 006° 48.120' W

52° 12.158' N, 006° 48.120' WThis is in the northeast corner at the head of the bay.

What is the initial fix?

The following Fethard-On-Sea initial fix will set up a final approach:

52° 11.490' N, 006° 48.586' W

52° 11.490' N, 006° 48.586' W What are the key points of the approach?

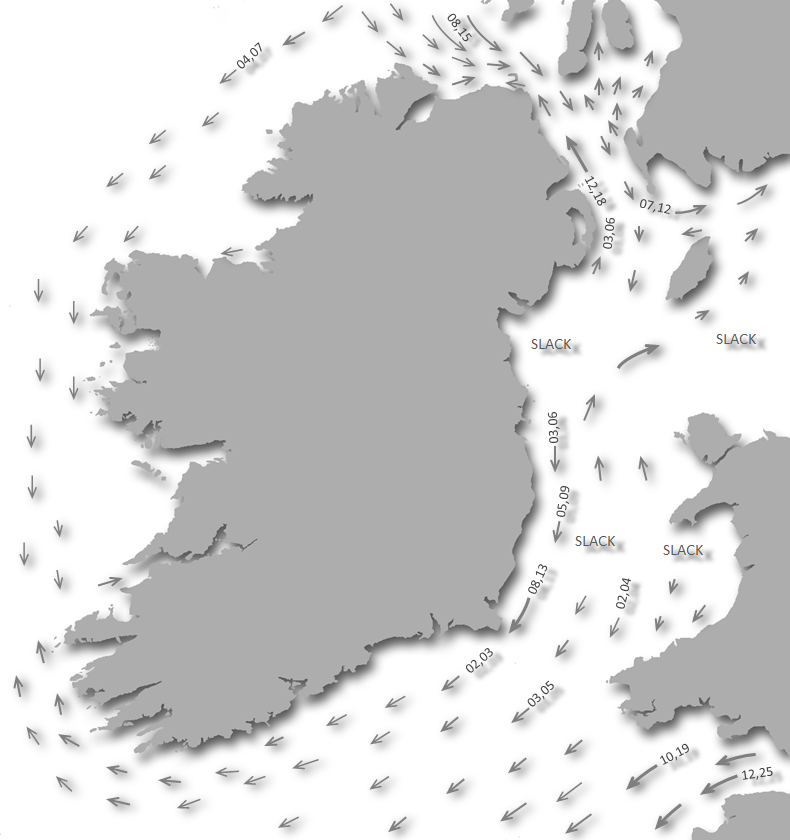

Offshore details are available in southeastern Ireland’s coastal overview for Rosslare Harbour to Cork Harbour  .

.

.

.Not what you need?

Click the 'Next' and 'Previous' buttons to progress through neighbouring havens in a coastal 'clockwise' or 'anti-clockwise' sequence. Below are the ten nearest havens to Bannow Bay for your convenience.

Ten nearest havens by straight line charted distance and bearing:

- Fethard On Sea - 0.9 nautical miles SW

- Baginbun Bay - 1.8 nautical miles SSW

- Dollar Bay - 4.1 nautical miles W

- Templetown Bay - 4.1 nautical miles WSW

- Lumsdin's Bay - 4.6 nautical miles SW

- Duncannon - 5.1 nautical miles WNW

- Creadan Head - 5.7 nautical miles WSW

- Slade - 5.7 nautical miles SW

- Arthurstown - 6 nautical miles WNW

- Ballyhack - 6.6 nautical miles WNW

These havens are ordered by straight line charted distance and bearing, and can be reordered by compass direction or coastal sequence:

- Fethard On Sea - 0.9 miles SW

- Baginbun Bay - 1.8 miles SSW

- Dollar Bay - 4.1 miles W

- Templetown Bay - 4.1 miles WSW

- Lumsdin's Bay - 4.6 miles SW

- Duncannon - 5.1 miles WNW

- Creadan Head - 5.7 miles WSW

- Slade - 5.7 miles SW

- Arthurstown - 6 miles WNW

- Ballyhack - 6.6 miles WNW

What's the story here?

Bannow Church with Baginbun Head in the background

Bannow Church with Baginbun Head in the backgroundImage: Michael Harpur

Bannow Bay is a remote and secluded bay located on the east side of the Hook Peninsula, 7 miles northeast of Hook Head Lighthouse. Baginibun Head, surmounted by a Martello Tower, forms the western boundary of the bay, with Clammers Point the eastern extremity. The area’s main settlement is the village of Carrig-on-Bannow, about a mile from the isolated bay.

Bannow Island and the tidal inlet within

Bannow Island and the tidal inlet withinImage: Michael Harpur

The bay provides a useful anchorage in clear sand off the shores of Bannow Island (now no longer an island as it is joined to the eastern mainland). An extensive tidal inlet, navigable only at high water, can be accessed between the western mainland and Bannow Island. With the benefit of local knowledge, a small shoal vessel can pass in and ascend as far as Clonmines.

How to get in?

Bannow Bay

Bannow BayImage: Michael Harpur

Use the Fethard

Use the Fethard  entry for seaward approaches and a description of the entrance. The Bay is entered between Innyard Point and Clammers Point, situated 1½ miles to the northeast on the bay’s eastern side. The navigable width between these two points is reduced to about a mile by the foul ground that extends 300 metres off Innyard Point, and the drying Selskar Rock situated 700 metres south by southwest of Clammers Point.

entry for seaward approaches and a description of the entrance. The Bay is entered between Innyard Point and Clammers Point, situated 1½ miles to the northeast on the bay’s eastern side. The navigable width between these two points is reduced to about a mile by the foul ground that extends 300 metres off Innyard Point, and the drying Selskar Rock situated 700 metres south by southwest of Clammers Point.  Selskar Rock, the outer rock just showing, as seen from the beach

Selskar Rock, the outer rock just showing, as seen from the beachImage: Michael Harpur

At about the midpoint of the two headlands is the covered Shoal Rock, located ½ mile east-northeast of Innyard Point. It has 1 metre of cover at LWS (0.3 LAT) and is of most concern at low water. Thus, with Shoal and Selskar Rocks mid and to the eastern half of the approach path, the best way into the head of Bannow Bay is on the western side, between Innyard Point and the easily circumvented Shoal Rock, where the Fethard initial fix provides a safe lead-in point.

Baginbun and Fethard as seen opposite Bannow Beach

Baginbun and Fethard as seen opposite Bannow BeachImage: Michael Harpur

From the initial fix proceed northeast until the small harbour of Fethard, close within Innyard Point, comes on the port beam. Then turn to starboard towards the 21-metre-high Bannow Island, now part of the mainland, situated at the head of the bay. The ruins of an old church will be seen close east of the island.

From the initial fix proceed northeast until the small harbour of Fethard, close within Innyard Point, comes on the port beam. Then turn to starboard towards the 21-metre-high Bannow Island, now part of the mainland, situated at the head of the bay. The ruins of an old church will be seen close east of the island.  Anchor over sand and land on the beach or at Fethard

Anchor over sand and land on the beach or at FethardImage: Michael Harpur

Anchor according to draught and conditions in sand. Be watchful of the effect of the in-draught of the tidal inlet as it can be felt for some distance outside. Land on the beach or at Fethard quay.

Anchor according to draught and conditions in sand. Be watchful of the effect of the in-draught of the tidal inlet as it can be felt for some distance outside. Land on the beach or at Fethard quay.At high water it is possible to enter the extensive tidal inlet situated at the head of the bay. This is achieved by crossing the sandbar close west of Bannow Island and following the channels within. It is riddled with sandbanks, however, that are subject to constant change. Although local boatmen do operate within Bannow’s tidal inlet, the area is best tackled with very accurate and current local knowledge, shallow draughts, plus a good measure of steely courage. The complexity of the channel structure around the sandbar, its shifting and unpredictable nature, and the speed of the currents make it an ill-advised endeavour for the visiting boatman.

The uninviting channel close west of Bannow Island that provides access to the tidal inlet

The uninviting channel close west of Bannow Island that provides access to the tidal inlet(as seen at low water)

Image: Michael Harpur

A determined skipper would have to personally chart the entrance and keep it current for the duration of the stay. Such an endeavour would mean working with local fishermen, walking the shorelines from either side, plus making extensive small boat trials in very settled conditions. Indeed, at the time of writing, the pattern of the entrance has switched after many decades from a wide eastern channel to a narrow, shallow western channel. This presents a new learning curve for local boatmen, let alone the unfamiliar. Only after some current data has been amassed can a skipper truly evaluate the wisdom of an attempt on the bar and the tidal inlet beyond.

Shoal-draught vessels in the tidal inlet

Shoal-draught vessels in the tidal inletImage: Michael Harpur

Vessels that enter the inlet will, however, find protection from almost any weather condition. It has also to be considered a ‘lock-in’ with southerly gales. The entrance at these times, encumbered with shoals with depths as little as 0.3 metres in the middle, presents a mass of broken water.

Why visit here?

Bannow, in Irish Banú, is derived from its ancient Irish name, Cuan-an-bhainbh, meaning ‘harbour of the sucking pig’ or ‘bonnive’. This is thought to refer to the original small island set into the fast-flowing tides of the tidal inlet behind. The area preserved the latter part of the name, which was anglicised to Bannow. At one time it was thought that this shortened name was derived from the Irish word for blessed, beannaighte, but this is not the case. Diarmait Mac Murchada

Diarmait Mac MurchadaImage: Public Domain

Norman soldiers from the time

Norman soldiers from the timeImage: Public Domain

Perpetually in battle with the native Welsh, Strongbow was an experienced military campaigner. His price was succession to kingship of Leinster upon Diarmait's death, which would be assured by marriage to Diarmait’s daughter Aoife upon conquest. Diarmait agreed and, with the promise of grants of lands, Strongbow brought in his half-brothers Robert Fitz-Stephen, a Norman-Welsh adventurer, and Fitz-Stephen’s half-brother Maurice FitzGerald, along with many other Cambro-Norman warlords. Fitz-Stephen was accompanied by his half-nephew, Robert de Barry. Diarmait also managed to secure the services of a group of Flemish mercenaries led by Richard Fitzgodebert de Roche, and they accompanied him when he returned to Ireland.

The Norman conquest of Ireland began upon Bannow Beach

The Norman conquest of Ireland began upon Bannow Beach Image: Michael Harpur

In this piecemeal fashion, and largely a family affair, the Norman conquest of Ireland began around 1 May 1169. Robert Fitz-Stephen brought up the single-masted longships on the beach at the foot of Bannow Island and landed a force of 30 knights, 60 men-at-arms and 300 bowmen. The following day two further ships arrived under the command of Maurice de Prendergast, landing 10 knights and 60 bowmen. Although small in number, it was militarily formidable and the numbers of the invasion force were soon bolstered by 500 soldiers commanded by Diarmait. The combined force then set out to take the semi-independent Norse-Gaelic seaport of Wexford.

Normans in battle

Normans in battleImage: Public Domain

The parish church of St Mary’s overlooking the landing beach

The parish church of St Mary’s overlooking the landing beachImage: Michael Harpur

After about three weeks of inactivity, Diarmait and Fitz-Stephen’s forces attacked territories on Leinster’s western border. By then the High King of Ireland, Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair, had mobilised and marched against them. Events played into Ua Conchobair’s hands and, faced by the prospect of being overwhelmed, de Prendergast and Diarmait allowed the Church to mediate and find a settlement via negotiations at Ferns. The terms agreed were that if Ua Conchobair was recognised as High King and the Normans were sent back to Britain, Diarmait was allowed to remain King of Leinster and granted freedom of action in south Leinster. Ua Conchobair was content with the agreement and, unaware of the strength of the Norman threat, he left with his army and relative peace followed. But Diarmait not only allowed the Normans to remain in Leinster, he immediately wrote to Strongbow to send reinforcements. The responding second wave of Norman landings would begin at Baginbun the following year. The invasion of Ireland would then begin in earnest and Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair would be its last High King.

St Mary’s Church

St Mary’s ChurchImage: Michael Harpur

So it began, almost exactly a century after the Battle of Hastings, where William the Conqueror routed Harold’s forces and began the systemic colonisation of England. It was now Ireland’s turn, where the Normans would create a medieval blueprint for aggressive colonialism that would bury itself deep in the Irish psyche. What is perhaps most strikingly overlooked in this story, is the first contact in Duncormick. It would have been little more than a brief skirmish for the advancing military machine, the likes of which Ireland would never have experienced. “[It] deserves greater respect in history than it has got,” noted the 1971 Capuchin Annual. “[For this was] the first battle of the Norman invasion, the first attempt to stop the foreigners, the first bloody encounter in a struggle which was to endure for 800 years.”

St Mary’s Church interior

St Mary’s Church interiorImage: Michael Harpur

The shores of Bannow Bay upon which the Milford Haven invasion boats arrived and first made camp were slightly different to what is experienced today. Bannow Island was then an easily defendable island separated from the mainland by a narrow eastern channel that has since silted up. The Normans went on to found a town on the island that grew to become a thriving seaport and market town. This all came to a halt late in the 14th century, when the then harbour silted up. The town nevertheless continued and was sending two representatives to the Irish Parliament until the Act of Union in 1801. After this time it gradually disappeared.

St Mary’s Church at dusk

St Mary’s Church at duskImage: Michael Harpur

Legend claims that the shifting sands of the estuary covered the remains of the town. The rough undulating ground to the front of the church is believed by some to be the result of this burial. The exact location of the town, however, is a matter of debate, folklore and the many legends that have grown around Bannow’s buried city.

Tintern Abbey sited within a grove of trees

Tintern Abbey sited within a grove of treesImage: Tourism Ireland

Only the ruins of the nave and chancel of the late 12th-century Norman Romanesque parish church of St Mary remain of the once-thriving town on Bannow Island. The fortified church was probably founded by monks from Canterbury and was under the Cistercians at Tintern Abbey from 1245. Much more of the latter Tintern Abbey remains on the west shore of Bannow Bay. William Marshal (Norman French Williame li Mareschal) built Tintern Abbey in 1200, romantically situated on the edge of a creek. Tintern was Marshal’s way of giving thanks for his rescue when his boat was caught in a storm off the Wexford coast. He populated the Abbey with monks from its famous namesake in Monmouthshire, Wales. Tintern Abbey was one of the most powerful Cistercian foundations in the southeast until the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1536 and its suppression in 1538. The remains, sited in a grove of trees with an old stone bridge leading across the fields down to Barrow Bay, can be visited today.

The remains of Tintern Abbey

The remains of Tintern AbbeyImage: Don Wright via CC BY 2.0

From a boating point of view, this is a useful anchorage and particularly so for a family boat, with its wonderful beach. But for those with any sense of history, this is a chance to anchor in a place that was a watershed in the history of Ireland, and experience it very little changed from when the Normans came ashore almost a millennium ago.

What facilities are available?

There are no facilities either outside or within the tidal inlet of Bannow Bay. Inside the tidal estuary there are indications of ‘St Paul’s Quay’, but this is only a collection of Rocks, albeit with a sealed access road down to the high-water shoreline. Boats that lie there have moorings and take a dingy to the shore, where road access is available at points inside the bay. Alternatively, it is possible to find an area where a vessel may dry out near the shoreline. Landing at Fethard provides reasonable facilities.Any security concerns?

Surrounded by provincial farmland, there are few boats or people travelling in this bay to cause trouble to a moored boat.With thanks to:

Declan Hearne, Long term fisherman and retired area Coastguard leader. Photography with thanks to Michael Harpur

About Bannow Bay

Bannow, in Irish Banú, is derived from its ancient Irish name, Cuan-an-bhainbh, meaning ‘harbour of the sucking pig’ or ‘bonnive’. This is thought to refer to the original small island set into the fast-flowing tides of the tidal inlet behind. The area preserved the latter part of the name, which was anglicised to Bannow. At one time it was thought that this shortened name was derived from the Irish word for blessed, beannaighte, but this is not the case.

Diarmait Mac Murchada

Diarmait Mac MurchadaImage: Public Domain

Norman soldiers from the time

Norman soldiers from the timeImage: Public Domain

Perpetually in battle with the native Welsh, Strongbow was an experienced military campaigner. His price was succession to kingship of Leinster upon Diarmait's death, which would be assured by marriage to Diarmait’s daughter Aoife upon conquest. Diarmait agreed and, with the promise of grants of lands, Strongbow brought in his half-brothers Robert Fitz-Stephen, a Norman-Welsh adventurer, and Fitz-Stephen’s half-brother Maurice FitzGerald, along with many other Cambro-Norman warlords. Fitz-Stephen was accompanied by his half-nephew, Robert de Barry. Diarmait also managed to secure the services of a group of Flemish mercenaries led by Richard Fitzgodebert de Roche, and they accompanied him when he returned to Ireland.

The Norman conquest of Ireland began upon Bannow Beach

The Norman conquest of Ireland began upon Bannow Beach Image: Michael Harpur

In this piecemeal fashion, and largely a family affair, the Norman conquest of Ireland began around 1 May 1169. Robert Fitz-Stephen brought up the single-masted longships on the beach at the foot of Bannow Island and landed a force of 30 knights, 60 men-at-arms and 300 bowmen. The following day two further ships arrived under the command of Maurice de Prendergast, landing 10 knights and 60 bowmen. Although small in number, it was militarily formidable and the numbers of the invasion force were soon bolstered by 500 soldiers commanded by Diarmait. The combined force then set out to take the semi-independent Norse-Gaelic seaport of Wexford.

Normans in battle

Normans in battleImage: Public Domain

The parish church of St Mary’s overlooking the landing beach

The parish church of St Mary’s overlooking the landing beachImage: Michael Harpur

After about three weeks of inactivity, Diarmait and Fitz-Stephen’s forces attacked territories on Leinster’s western border. By then the High King of Ireland, Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair, had mobilised and marched against them. Events played into Ua Conchobair’s hands and, faced by the prospect of being overwhelmed, de Prendergast and Diarmait allowed the Church to mediate and find a settlement via negotiations at Ferns. The terms agreed were that if Ua Conchobair was recognised as High King and the Normans were sent back to Britain, Diarmait was allowed to remain King of Leinster and granted freedom of action in south Leinster. Ua Conchobair was content with the agreement and, unaware of the strength of the Norman threat, he left with his army and relative peace followed. But Diarmait not only allowed the Normans to remain in Leinster, he immediately wrote to Strongbow to send reinforcements. The responding second wave of Norman landings would begin at Baginbun the following year. The invasion of Ireland would then begin in earnest and Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair would be its last High King.

St Mary’s Church

St Mary’s ChurchImage: Michael Harpur

So it began, almost exactly a century after the Battle of Hastings, where William the Conqueror routed Harold’s forces and began the systemic colonisation of England. It was now Ireland’s turn, where the Normans would create a medieval blueprint for aggressive colonialism that would bury itself deep in the Irish psyche. What is perhaps most strikingly overlooked in this story, is the first contact in Duncormick. It would have been little more than a brief skirmish for the advancing military machine, the likes of which Ireland would never have experienced. “[It] deserves greater respect in history than it has got,” noted the 1971 Capuchin Annual. “[For this was] the first battle of the Norman invasion, the first attempt to stop the foreigners, the first bloody encounter in a struggle which was to endure for 800 years.”

St Mary’s Church interior

St Mary’s Church interiorImage: Michael Harpur

The shores of Bannow Bay upon which the Milford Haven invasion boats arrived and first made camp were slightly different to what is experienced today. Bannow Island was then an easily defendable island separated from the mainland by a narrow eastern channel that has since silted up. The Normans went on to found a town on the island that grew to become a thriving seaport and market town. This all came to a halt late in the 14th century, when the then harbour silted up. The town nevertheless continued and was sending two representatives to the Irish Parliament until the Act of Union in 1801. After this time it gradually disappeared.

St Mary’s Church at dusk

St Mary’s Church at duskImage: Michael Harpur

Legend claims that the shifting sands of the estuary covered the remains of the town. The rough undulating ground to the front of the church is believed by some to be the result of this burial. The exact location of the town, however, is a matter of debate, folklore and the many legends that have grown around Bannow’s buried city.

Tintern Abbey sited within a grove of trees

Tintern Abbey sited within a grove of treesImage: Tourism Ireland

Only the ruins of the nave and chancel of the late 12th-century Norman Romanesque parish church of St Mary remain of the once-thriving town on Bannow Island. The fortified church was probably founded by monks from Canterbury and was under the Cistercians at Tintern Abbey from 1245. Much more of the latter Tintern Abbey remains on the west shore of Bannow Bay. William Marshal (Norman French Williame li Mareschal) built Tintern Abbey in 1200, romantically situated on the edge of a creek. Tintern was Marshal’s way of giving thanks for his rescue when his boat was caught in a storm off the Wexford coast. He populated the Abbey with monks from its famous namesake in Monmouthshire, Wales. Tintern Abbey was one of the most powerful Cistercian foundations in the southeast until the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1536 and its suppression in 1538. The remains, sited in a grove of trees with an old stone bridge leading across the fields down to Barrow Bay, can be visited today.

The remains of Tintern Abbey

The remains of Tintern AbbeyImage: Don Wright via CC BY 2.0

From a boating point of view, this is a useful anchorage and particularly so for a family boat, with its wonderful beach. But for those with any sense of history, this is a chance to anchor in a place that was a watershed in the history of Ireland, and experience it very little changed from when the Normans came ashore almost a millennium ago.

Other options in this area

Click the 'Next' and 'Previous' buttons to progress through neighbouring havens in a coastal 'clockwise' or 'anti-clockwise' sequence. Alternatively here are the ten nearest havens available in picture view:

Coastal clockwise:

Fethard On Sea - 0.6 miles SWBaginbun Bay - 1.1 miles SSW

Slade - 3.5 miles SW

Lumsdin's Bay - 2.9 miles SW

Templetown Bay - 2.6 miles WSW

Coastal anti-clockwise:

Georgina’s Bay - 5.4 miles SEGilert Bay - 5.4 miles SE

Great Saltee (landing beach) - 5.3 miles SE

Kilmore Quay - 5.1 miles ESE

Little Saltee (west side) - 5.4 miles ESE

Navigational pictures

These additional images feature in the 'How to get in' section of our detailed view for Bannow Bay.

| Detail view | Off |

| Picture view | On |

Add your review or comment:

Please log in to leave a review of this haven.

Please note eOceanic makes no guarantee of the validity of this information, we have not visited this haven and do not have first-hand experience to qualify the data. Although the contributors are vetted by peer review as practised authorities, they are in no way, whatsoever, responsible for the accuracy of their contributions. It is essential that you thoroughly check the accuracy and suitability for your vessel of any waypoints offered in any context plus the precision of your GPS. Any data provided on this page is entirely used at your own risk and you must read our legal page if you view data on this site. Free to use sea charts courtesy of Navionics.